The 15 Most Fascinating New York Real Estate Cases of the 21st Century

By Daniel Edward Rosen and Daniel Geiger August 8, 2012 7:15 am

reprints

For better or worse, even New York’s healthiest buildings—those assets that manage to avoid over-leveraging and shoddy craftsmanship—live and breathe thanks to armies of real estate lawyers, responsible for everything from debt originations and litigation to tenant-landlord disputes and bankruptcy filings. Indeed, for every real estate developer trumpeted in the daily newspapers, you can bet a couple dozen are standing right behind him, making sure he’s protected from attackers in one of New York’s most perilous industries. After surveying a dozen of the most visible real estate lawyers in town and whittling from a list of more than 30 notable cases, we bring you our highly subjective list of the 15 most fascinating New York real estate cases of the 21st century. —Jotham Sederstrom, Editor

For better or worse, even New York’s healthiest buildings—those assets that manage to avoid over-leveraging and shoddy craftsmanship—live and breathe thanks to armies of real estate lawyers, responsible for everything from debt originations and litigation to tenant-landlord disputes and bankruptcy filings. Indeed, for every real estate developer trumpeted in the daily newspapers, you can bet a couple dozen are standing right behind him, making sure he’s protected from attackers in one of New York’s most perilous industries. After surveying a dozen of the most visible real estate lawyers in town and whittling from a list of more than 30 notable cases, we bring you our highly subjective list of the 15 most fascinating New York real estate cases of the 21st century. —Jotham Sederstrom, Editor

Not to mention the very future of the trophy asset at the center of the dispute. The case began in 2009, months after Extell Development and the Carlyle Group missed a Sept. 1, 2008, closing deadline tied to new condos at the Rushmore, the 289-unit luxury building at 80 Riverside Boulevard that, two years earlier, drew intense interest at the height of the bubble.

But when the economy soured shortly after a Sept. 15 bankruptcy claim by Lehman Brothers, jittery buyers—initially 23 of them, paying some $10 million in deposits on nearly $70 million in condominiums—demanded refunds, insisting that after missing the Sept. 1 closing date printed in offering plans, Extell Development was required not only to submit a new operating budget for the building but also to allow jittery buyers the right to rescind their contracts. Lawyers from Stroock & Stroock representing Extell fought back, arguing that Sept. 1, 2008, was the first day of the budget year, not the last, and was therefore a typographical error. Instead, it should have stated that buyers had the right to back out if a closing didn’t occur by Sept. 1, 2009.

In April 2010, then-New York State Attorney General Andrew Cuomo, already in the process of campaigning for governor, ruled in favor of the buyers, now numbering more than 40. For those complainants, the decision capped what had, by then, spiraled into an 16-month feud.

For Extell Development and president Gary Barnett, however, the case was just warming up. Calling for a reversal of the April 2010 ruling, Mr. Barnett, through the law firm Boies, Schiller & Flexner LLP, argued that the developer had never been given an opportunity to cross-examine buyers or collect evidence to bolster its defense.

But despite the lawsuits that followed, it’s possible that today—two years after the AG ruling—more people know the luxury property for its satisfied buyers: After all, when Yankees slugger Alex Rodriguez left 15 Central Park West, he headed east, to the Rushmore.

In 2008, the economy collapsed into a deep recession and the residential real estate market in the city came crashing down. The situation seemed especially dire and cruel for condo buyers who were under contract to purchase an apartment. Though these buyers hadn’t yet completed their acquisitions, they had pledged nonrefundable down payments of tens or even hundreds of thousands of dollars to buy apartments that were suddenly worth 40 percent less.

Then Adam Leitman Bailey, a real estate attorney in Manhattan, came up with a novel solution. Mr. Bailey, in collaboration with other lawyers at his eponymously named firm Adam Leitman Bailey PC, noticed that contracts at numerous condo buildings did not conform to an obscure federal law passed in 1968 called the Interstate Land Sales Act.

The rule required developers to provide disclosure documents. Many developers had given borrowers the forms, but Mr. Bailey noticed that they often had not been prepared properly when they were filed with the city to record a condo’s sale. One of the first cases in which Mr. Bailey unveiled his argument concerned a $3.4 million condo that Greek shipping magnate Vasilis Bacolitsas had purchased in a high-end Upper East Side building developed by Related. What seemed like a long shot turned into a victory that stunned the real estate world and suddenly opened the floodgates for Mr. Bailey and other attorneys to try to nullify other sales contracts around the city.

In practice, Mr. Bailey said, the ruling allowed most buyers the leverage to renegotiate with developers and receive a discount to go forward with their purchases. He estimates he represented about 1,000 buyers who received discounts.

“It helped the buyers, and really it also helped developers, because after the ruling, it gave them the ability to go to their lenders and say ‘hey, we have to lower prices,’” Mr. Bailey said. “Many developers couldn’t negotiate with buyers before this, because their lenders wouldn’t let them slash prices.”

Ironically, Related appealed the decision with Mr. Bacolitsas that got ILSA cases off the ground, and that suit has yet to be sorted out.

“Whatever the outcome of that case, ILSA’s time has passed,” Mr. Bailey said. “All developers conform with it now, and prices have rebounded. It was a tool that worked during the downturn.”

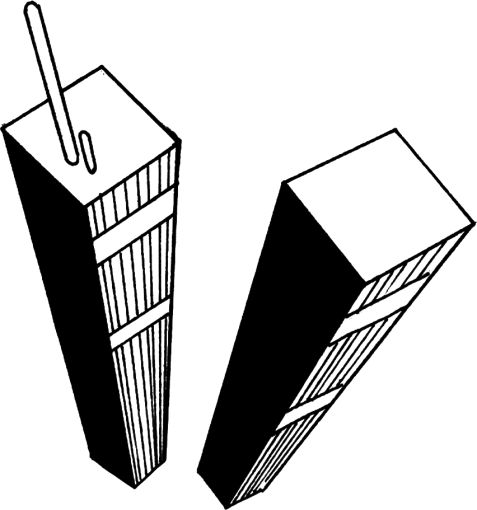

In a series of lawsuits, the developer had argued that his company, Silverstein Properties, was entitled to a double payment of $7 billion because the attacks constituted two separate occurrences, not just one.

Swiss Re, one of nearly a dozen insurers involved in the suit, argued that the attack, because it was part of an orchestrated plan, constituted a single event and therefore qualified Mr. Silverstein for only the face value of his $3.5 billion insurance policy on the fallen towers.

In the end, Mr. Silverstein lost one verdict and won one verdict for a total payout of $4.6 billion. But for real estate owners, lenders and brokers, the repercussions were felt within months of when the towers fell.

Indeed, as described by several lawyers involved in real estate transactions months after the attacks, a new fact of life, terrorism coverage, permeated the landscape, with real estate buyers and sellers, not to mention lawyers and insurance providers, scrambling to understand new federal legislation that rewrote insurance policies, legal scholars familiar with the changes told The Commercial Observer.

Among the first properties to change hands following the attacks was 1515 Broadway, which the real estate investment trust SL Green closed on in the early months of 2002. In order to close the deal, however, the REIT and its lawyers had to navigate entirely new language in otherwise boilerplate insurance policies, including new contingencies regarding the terrorism coverage itself.

“There had never been a terrorism policy before this, so nobody really knew what it would look like,” said the lawyer. “This was completely unprecedented.” Since then, of course, hundreds of deals have been closed across New York City—and in every sale, insurance policies and lending agreements now boast terrorism clauses.

It was from that business model—multiple retailers under one roof, construction financed by a single user—that the brothers Bucksbaum created the modern shopping mall, a totem of commerce so potent today that, from Montpelier to Chattanooga, teenagers now regard them less as brick-and-mortar assets than actual monuments to capitalism—complete with jewelry kiosks.

By 1970, the brothers recognized that desire and renamed their company General Growth Properties, a force of nature that, over the next 42 years, pockmarked approximately 43 states with malls while boasting nearly 2 billion visitors—annually—at 169 sites.

It was from those heights that GGP, then the nation’s second-largest mall operator, found itself dangling by a thread one day in 2008, just after defaulting on $900 million in loans—a fraction of the $25 billion in mostly short-term mortgage debt the company reported two months earlier.

The ensuing Chapter 11 filing in 2009 was heralded by analysts as one of the most devastating commercial real estate collapses in U.S. history, while others described a precedent-setting court decision that sent tremors across the lending community.

At the heart of the case was the so-called single purpose entity designation General Growth Properties set up in order to securitize loans, which required the creation of an independent board of directors beholden neither to GGP’s CEO or the dozens of lenders it was doing business with. Although such a designation is common among borrowers—it was famously used for duplicitous reasons by Enron—what was far more unlikely until then was the decision by General Growth Properties’ chief executive, Adam Metz, to fire the company’s independent board.

“What happened was the CEO at the time fired the independent directors and replaced them with GGP-friendly directors, and then got them to vote for a bankruptcy filing,” said one real estate lawyer who did not work on the case but, like many in the industry, watched it closely. “That was a way to get around this independent director concept that was so embedded in the way real estate loans were made that, until now, nobody had the nerve to try and circumvent it.” Such chutzpah, while not against the law, prompted lenders across the country to wonder if more companies would simply install friendly directors to do their bidding, although most concede that, thus far, few have followed General Growth Properties’ lead.

510 Madison Avenue was a roughly 400,000-square-foot building that Mr. Macklowe and his son Billy Macklowe envisioned during boom times as an irresistible draw for deep-pocketed boutique financial firms.

When the recession hit, however, rents plummeted, leasing deals withered, financial firms stopped taking space and 510 Madison Avenue seemed like a sitting duck for a forcible takeover.

SL Green, the powerful real estate investment trust and the city’s biggest commercial landlord, was eager to pounce. The company bought up both senior and mezzanine debt on the tower and aimed to take control by citing an appraisal it commissioned that showed the building’s value had dipped below certain thresholds in the loans.

With creditors circling and his financial wherewithal in question, Mr. Macklowe had difficulty attracting tenants at just the moment he needed them most. Meanwhile, a fire at the property in early 2009 set back construction and created yet another obstacle.

“Harry built that beautiful building, then it had the fire and he had to repair all of that damage, and he understandably ran out of term on his loan,” said Stephen Meister, Mr. Macklowe’s lawyer in the subsequent foreclosure case with SL Green. “I think we showed that SL Green was buying up the debt on the property not to be a lender, but to foreclose on the properties.”

Mr. Meister eventually won Mr. Macklowe an extension, a victory that allowed him to recapitalize the property with Boston Properties.

The piece wasn’t intentional: New York City sought to widen Houston Street in the 1940s and destroyed the building adjacent to the one that holds the work now. The interior wall and structure of the destroyed building remained attached to the façade of the neighboring one, 599 Broadway. City Walls, an organization that later became the Public Art Fund, was brought in to figure out a solution. City Walls envisioned a contemporary masterpiece, raised $10,000, and installed the Gateway to SoHo in 1973.

The piece was set in place by Forrest Myers, a New York sculptor, and consisted of 42 aluminum bars attached to 42 steel braces.

The legal struggle didn’t start until the building was sold and turned into a condominium. David Topping, the new owner, filed a lawsuit claiming that the installation prevented them from displaying billboards that could earn upward of $600,000 a year. The Landmarks Commission said that nothing could be done to the piece, so Mr. Topping dragged the commission, the city and Forrest Myers into the courtroom.

The judge ruled in favor of Mr. Topping, undermining and shattering the commission’s efforts to preserve and protect historic and public artworks throughout the city. The Gateway to SoHo was taken down in 2002 as the building worked on exterior repairs.

In 2007, the artwork was revived as the owners of 599 Broadway, Mr. Myers and New York City finalized a deal. The deal would extend the wall by 30 feet, essentially raising the artwork, so that the street-level exterior could be used for advertising. The owners also agreed to pay for maintenance and restoration costs.

Further, the lawyers for 599 Broadway put an unusual offer on the table: If someone or a group pays the value of the advertising revenue, then the advertising will be permanently removed.

Designed by French architect Jean Nouvel, the glass tower offered MoMA 52,000 square feet of additional gallery space while promising an “exhilarating” addition to Manhattan’s skyline, as The New York Times predicted in an architectural review at the time.

But before the structure could even be built, Mr. Nouvelle and Hines were faced with navigating four separate zoning districts and a plot of land in close proximity to two landmarked sites, St. Thomas Church and The University Club, and a residential portion on the 54th Street side of the L-shaped plot.

Lawyers with Kramer Levin Naftalis & Frankel, working on behalf of MoMA and with the developers, saw that the building could be erected by using both landmarked sites’ unused air rights while positioning the building away from Sixth Avenue. The final design was a building that looked as though Mr. Nouvelle “extruded it like a piece of taffy,” said a person close to the development, who asked not to be named.

The 54-55 Street Block Association voiced its disapproval of the “exceedingly tall tower,” but all that opposition led to was eventual approval by the New York City Council, with a provision that the tower be chopped down by at least 200 feet.

“The 53rd Street project demonstrates that even in the most challenging situation with multiple zoning districts, nearby landmarks, a museum’s needs and concerned neighbors, it is still possible to use the New York land-use process to create a great building and great architecture,” said Samuel Lindenbaum, a lawyer at Kramer Levin who represented MoMA in the deal.

Such appeared to be the case when Stephen Ross, chief executive of the Related Companies, bought $250 million of debt on the office building 3 Columbus Circle in 2010 and stated during an interview his intention to build something better on the site.

3 Columbus Circle, formerly known as 1775 Broadway, was an office property purchased in 2004 by developer Joe Moinian, who envisioned overhauling it with an all-new glass façade and other renovations so it could receive higher-tier rents.

The project stalled during the downturn, when Mr. Moinian fell into default on his debts at the property. Mr. Moinian eventually managed to maintain control of the property by bringing in SL Green as a partner, but not before he and Mr. Ross faced off in the courtroom.

In that suit, Mr. Ross’s attorneys insisted in late 2010 that Mr. Moinian owed a roughly $54 million prepayment penalty to recapitalize the project with SL Green’s money, a claim that Mr. Moinian’s attorney in the case, Stephen Meister, called the “most egregious case of predatory lending” he had ever seen, according to reports.

Mr. Ross and Mr. Moinian eventually settled the case, with Mr. Moinian and SL Green paying off the loan as well as interest payments while avoiding the $54 million fee. Under the leasing stewardship of SL Green, the once nearly vacant property went on to have leasing success, signing a roughly 300,000-square-foot deal with the advertising company Young & Rubicam earlier this year.

As local developer Robert Congel, head of the Pyramid Companies, claimed in his lawsuit against a lender, Destiny USA “was designed to serve as a ‘living laboratory’ and showcase for the use of state-of-the-art ‘green’ technology.” It added that the project would “create tens of thousands of jobs [and] attract millions of visitors to an economically challenged region.”

But to realize this vision, the Pyramid Companies would first have to deal with an angry lender in Citigroup. The bank had accused the company of using most of its multimillion-dollar construction loan on needless expenses like pricey marketing professionals and “marketing gimmicks” (like painting the building green, the bank claimed) without securing even a single tenant for the new project—an overrun that the bank argued was worth $18 million.

After it had lent Pyramid Cos. $85 million of its $155 million construction loan for the project, Citigroup turned off the tap, so to speak.

“Due to considerable cost overruns, schedule delays and inability to secure a single lease, despite Citi’s efforts, there is no possibility the project will be completed unless the borrower meets its obligation to make additional funds available,” the bank said at the time. Pyramid Cos. struck back, suing Citigroup for defaulting on its construction loan agreement. In response to the suit, Citigroup’s attorney Leslie Fagen said to state Supreme Court Judge John Cherundolo, “they’re asking you to order us to fund a failure.”

Whether Judge Cherundolo saw the project as a failure is unknown, but he did order the bank to resume its financing of construction on Destiny USA. Appellate judges upheld the ruling, adding that financing must resume once Destiny USA posted a $15 million bond. In May 2011, construction on the Destiny USA project resumed, while Citigroup reached an agreement with Mr. Congel to cap its loans at the $86.6 million it already financed the project with, according to documents obtained by The Post-Standard. The development eventually signed a handsome mix of retail tenants, like J.Crew and Mr. Smoothie, and was opened to shoppers in November 2011. In March of this year, perhaps scarred by his experience, Mr. Congel was reported to have sworn off adding a hotel and more retail space to Destiny USA.

A recent suit, though, looks to have finally upended the duo’s hold on their collection of assets. In 2011, Joseph Tabak, a real estate investor who operates the firm Princeton Holdings, and investor Bluestone Group reached an agreement to buy Michael Ring’s share in the properties for $112.5 million.

The stake was meaningful. By taking over Michael’s share, Mr. Tabak and his partners could, by their rights as a stakeholder, force sales of the properties one by one, conceivably giving them the power to either swap out Frank Ring with another partner or consolidate the buildings fully under their own ownership. When Mr. Tabak moved to proceed with the transaction in February of that year, however, Michael Ring backed out of the agreement, sparking a lawsuit.

“Michael Ring just can’t go through with an agreement,” Janice Mac Avoy, a top litigator with the firm Fried Frank who represented Mr. Tabak in the suit, told The Commercial Observer. “He can’t follow through with doing leasing deals for his properties, and he didn’t want to follow through with the arrangement to sell his stake.”

In April of this year, an arbitrator sided with Mr. Tabak, giving him the right to buy out Michael Ring. The ruling would appear to be the opening step in unraveling the Rings’ hold on the properties.

“I think Joe underestimated getting involved with Michael; we thought the fight would be with Frank,” Ms. Mac Avoy said. “But we’ll find out. We’re going to start bringing these actions to force the sales.” Mr. Tabak’s possible acquisition and redevelopment of the Ring portfolio would bring an end to years of speculation about what would happen to the assets. Numerous developers and investors have viewed the properties as attractive investment opportunities. “There are a lot of people who would love to buy their buildings,” Robert Ivanhoe, an attorney with Greenberg Traurig, said. “I remember calling Michael Ring one time just to discuss a client I had who was interested in the properties, I think, or because I had some thought of what they could do with them, and he just started yelling and screaming at me. ‘Leave me alone! I’m not talking about anything! You have no business even to call me! Who do you think you are?!’ The guy just went ballistic.” Michael Ring did not return calls for comment.

Instead, it set off a maelstrom of legal headaches for its new owners, whose purchase of the 56-building complex was heralded as the biggest in United States history, and for anyone fighting to take ownership of the embattled private residential development at the center of it all.

In 2010, PSW NYC, a limited liability company set up by Pershing Square Capital Management and Winthrop Realty Trust, aimed to take over the property by snapping up the $300 million in defaulted senior mezzanine debt for just $45 million. At the same time, the trustees for that senior debt, Bank of America and U.S. Bancorp, were also looking to foreclose on the property (through CW Capital Asset Management, which took over the property from Tishman Speyer and owned mortgages on it in excess of $3 billion). CW Capital insisted that PSW, if it wanted to foreclose, had to pay off the senior mortgage and could not conduct future bankruptcy proceedings on Stuyvesant Town unless those senior loans had been paid off. New York State Supreme Court Justice Richard Lowe agreed with CW Capital’s argument, ruling that PSW could not foreclose on the property unless it paid off the entire $3.66 billion on the outstanding mortgage loan.

Stuyvesant Town’s tenants had their own legal issues, too. In 2007, a group of residents filed its own lawsuit against Tishman Speyer and MetLife, the building’s landlord prior to the Tishman Speyer purchase, claiming they had abused the J-51 Program (a city initiative that offers tax incentives to owners in exchange for apartment renovations) by overcharging their rents (their rents had changed from rent controlled to market rate). The tenants, led by Amy Roberts, argued that their landlord could not alter their rents to market rate until after the J-51 benefits expire in 2017.

The New York State Court of Appeals eventually ruled in the tenants’ favor, saying those free-market tenants were subject to illegal rent overcharges and were entitled to $215 million in rent rebates.

But with few exceptions, the cadre of judges who ruled on the case between 2003 and 2011 has thought differently, deciding that, besides seizing property from residents in Prospect Heights, the powerful Cleveland-based developer should go ahead with plans to build in one of Brooklyn’s most congested neighborhoods, bypass city land-review procedures and amend many of its original plans.

A group of rent stabilized tenants near the arena’s footprint and Develop Don’t Destroy Brooklyn, one of the most visible opponents of the project, filed approximately eight lawsuits over six years, charging the developer with a litany of accusations, including failing to provide an independent appraisal of the yards.

And while the opponents have claimed several small victories, the developer and its supporters have declared victory in nearly two dozen cases.

Despite the deluge of legal attacks, the Brooklyn Nets season opener is set to happen this fall. But even before that happens, Jay-Z, the hip-hop impresario and Brooklyn Nets investor, is set to perform at the Barclays Center later this month.

In something akin to a lending domino effect, the Philadelphia-based private equity group LEM Mezzanine took control of the 270-room hotel in late 2009 after winning it for a mere $2 million—and the assumption of $212 million in debt—at a foreclosure auction. The property had been brought to auction only a few months earlier, when Istithmar, the private equity arm of the government-backed Dubai World, defaulted on a $117 million mezzanine loan it had secured only a few years prior, in 2006.

But by March 2010, LEM Mezzanine, which itself had not submitted mezzanine loan payments since October 2009, filed for bankruptcy protection in connection with the asset—one day before the senior lender on the property, DekaBank, signaled that it would auction off yet another loan on the property.

The whirlwind of paper trading, of course, kept real estate attorneys buried under legal documents for years, each struggling to untangle multiple tranches of debt on the failed property at 201 Park Avenue.

In the end, Host Hotels took over the hotel and found new financing from a new mezzanine lender, Union Square Real Holding Corporation. In a statement in 2010, LEM Mezzanine celebrated the W Hotel’s latest sale. It was “accomplished through the cooperation of all of the parties,” according to the statement, and would “result in the winding up of the bankruptcy cases relating to the W New York.”

The hotel, a neo-Renaissance construction at Broadway between 61st and 62nd Streets, boasted its own rich history dating back to 1926, when it was designed and constructed by Emery Roth. It was well known among out-of-towners as the place to stay for the Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade, as its views overlooked not only the parade route but Central Park as well. The building, qualifying under rent regulatory laws, eventually had several rent-controlled and rent-stabilized tenants—an obstacle all too common in Manhattan real estate. The laws stipulate near-impossible eviction, leaving many development companies to settle with tenants in a lawyer’s office.

As a prudent company, Zeckendorf Development thoroughly discussed the potential costs of buyouts and relocation in advance with its attorney. Sherwin Belkin of Belkin Burden Wenig & Goldman LLP was brought on to finalize settlements for the remaining tenants. Not all tenants were persuaded by sheer money, either. One tenant, in addition to receiving payment, was relocated to another residence, where he lived until he passed away. Another was discovered not to be the primary resident and was brought into litigation. When there were only a few remaining tenants, the developer filed for permission to force them out through the Division of Housing and Community Renewal.

Given the provisions in the rent-regulation laws enacted in 1971, most of the tenants had lived there for over 40 years. Mr. Belkin noted that there were times when he brought in social workers and psychologists to help the tenants deal with the anxiety of moving elsewhere.

The number of rent-regulated apartments have dwindled over the years as tenants have moved out and passed away. The laws have also changed—a round of deregulation procedures was enacted in the early ’90s. But there are still nearly 40,000 rent-controlled units in the city, and they will surely be an obstacle for developers in the coming decades.